Waalo

Kingdom of Walo Waalo | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13th-14th century–1855 | |||||||||

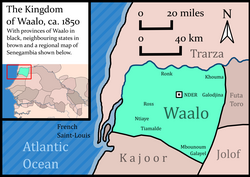

Waalo ca. 1850 | |||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Ndiourbel; Ndiangué; Nder | ||||||||

| Common languages | Wolof | ||||||||

| Religion | African traditional religion; Islam | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Brak | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Waalo founded by Ndiadiane Ndiaye | 13th-14th century | ||||||||

• part of the Jolof Empire | c. 1350-1549 (de facto) / 1715 (de jure) | ||||||||

• French colonization | 1855 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Waalo (Wolof: Waalo) was a kingdom on the lower Senegal River in West Africa, in what is now Senegal and Mauritania. It included parts of the valley proper and areas north and south, extending to the Atlantic Ocean. To the north were Moorish emirates; to the south was the kingdom of Cayor; to the east was Jolof.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]Oral histories claim that, before becoming a kingdom, the area of Waalo was ruled by a patchwork of Lamanes, a Serer title meaning the original owner of the land.[1] Etymological evidence suggests that the area was ruled by the Jaa'ogo dynasty of Takrur.[2] This aligns with early Arabic written sources which describe an island town known as Awlil (Waalo) near the mouth of the Senegal river, in a region called Senghana.[3][4]

Founding

[edit]The exact founding date of Waalo is debated by historians, but is associated with the rule of the first king, the semi-legendary Ndiadiane Ndiaye, in the 13th or 14th century.[5][6][7] Ndiaye, originally a Fula from Takrur, united the Lamanes and ruled Waalo for 16 years as an arbiter or judge rather than king before, according to some oral accounts, being driven out by his half brother Barka Bo, or Barka Mbodj. After this, Ndiaye took control of Jolof and founded the Jolof Empire.[8][1] Barka Mbodj was the first ruler to use the royal title 'Brak'.[9] Ndiaye eventually made Waalo a vassal.[10]

Europeans first appeared off the coast of Waalo in the 15th century, and soon began trading. This caused a significant shift in economic power away from the Jolof heartland towards coastal vassals such as Waalo and Cayor. Buumi Jelen, a member of the royal family, may have established his own control over Waalo during this period, and is credited with creating a system of alkaldes who served as customs collectors for the Buurba Jolof. He later attempted to ally with the Portuguese to take power, but was killed by his erstwhile allies in a dispute.[11]

The Jolof empire broke up in the aftermath of the battle of Danki in 1549, though the Brak continued to pay symbolic tribute to the Bourba Jolof until 1715.[12]

The French and the Desert

[edit]In 1638, the French established the first permanent European trading settlement at the mouth of the Senegal River, moving to the site of Saint-Louis in 1659 while facing consistent military and political pressure from the Brak.[13] The French presence would have a decisive effect on the rest of the history of Waalo.

Partly in response to the shift in trade away from Berber tribes to the French, Nasr ad-Din, a Berber Marabout, launched the Char Bouba War or the Marabout War, overthrowing the ruling aristocracy of Waalo (among other Senegal river kingdoms) in an attempt to establish an Islamic theocracy. Upon his death in 1674, however, his movement collapsed and the old hierarchies, aligned with Arab Hassan tribes north of the river and vigorously supported by the French, re-asserted themselves.[14][15]

During this same period, Moroccan forces came south to the Senegal river, forcing the Brak to move the capital from Ngurbel to the south bank and permanently breaking the kingdom's control on the north side.[16]

A Regional Power

[edit]In another attempt to further strengthen their economic position in the Senegal valley, in 1724 the French allied with Maalixuri, the lord of Bethio, to pressure the Brak Yerim Mbyanik and the Emirate of Trarza into concessions. His attempt at secession from Waalo failed when the French company stopped their support. By 1734 Yerim Mbyanik had the most powerful army in the region.[17] His rule and that of his two successors, Njaam Aram Bakar and Naatago Aram, was the apogee of Waalo-Waalo power.

Through the middle decades of the 18th century, Waalo exerted hegemony over the entire Senegal estuary and dominated Cayor as well. When the English took Saint-Louis in 1758 they found that the Brak had total control over river trade. Naatago repeatedly demanded increases in customs payments and slave prices, and blockaded the island when necessary.[18] In 1762 he appropriated payments from Cayor intended for Saint-Louis, and two years later invaded.[19]

Decline

[edit]In 1765 the Damel of Cayor counterattacked, armed with English guns, and soundly defeated the Waalo-Waalo.[19] After Naatago's death in 1766 a long civil war broke out, with the Moors constantly intervening and raiding. In 1775 the English took more than 8000 slaves from Waalo in less than six months.[18]

With recurring civil war and frequent foreign meddling in succession disputes, Waalo's power declined progressively in favor of the Moorish Emirate of Trarza.[20]

In the 1820s the marabout of Koki Ndiaga Issa, who had amassed significant political power in Cayor, was driven out by the damel. His forces, led by general Dille Thiam, took control of Waalo instead. The French intervened however, and killed Thiam.[21]

To stop the cripplying Moorish raids and present a unified front against the French, the Lingeer Njembot Mbodj married the Emir of Trarza in 1833. Faced with an alliance that could threaten the survival of the colony, Saint Louis attacked Waalo, deepening the long-running crisis. Njembot Mbodj was succeeded by her sister Ndate Yalle in 1847, but the French finally conquered the kingdom in 1855.[22][23]

Society

[edit]Government

[edit]The royal capital of Waalo was first Ndiourbel (Guribel) on the north bank of the Senegal River (in modern Mauritania), then Ndiangué on the south bank of the river. The capital was moved to Nder on the west shore of the Lac de Guiers.

Waalo had a complicated political and social system, which has a continuing influence on Wolof culture in Senegal today, especially its highly formalized and rigid caste system. The kingdom was indirectly hereditary, ruled by three matrilineal families: the Logar, the Tedyek, and the Joos, all from different ethnic backgrounds. The Joos were of Serer origin. This Serer matriclan was established in Waalo by Lingeer Ndoye Demba of Sine. Her grandmother Lingeer Fatim Beye is the matriarch and early ancestor of this dynasty. These matrilineal families engaged in constant dynastic struggles to become "Brak" or king of Waalo, as well as warring with Waalo's neighbors. The royal title "Lingeer" means queen or royal princess, used by the Serer and Wolof. Several Lingeer, notably Njembot Mbodj and Ndaté Yalla Mbodj ruled Waalo in their own right or as regents.[24]

The Brak ruled with a kind of legislature, the Seb Ak Baor, that consisted of three great electors who selected the next king. Their titles come from Pulaar terms that initially meant 'masters of initiation', and originate from the period before Ndiadiane Ndiaye when Takrur dominated the area.[2] There was also a complicated hierarchy of officials and dignitaries. Women had high positions and figured prominently in the political and military history of Waalo.

Provinces were ruled by semi-independent Kangam, such as the Bethio. Shifting allegiances between these powerful nobles, the Brak, other kingdoms, and the French of Saint-Louis led to a series of civil wars.[25]

Religion

[edit]Waalo had its own traditional African religion. Islam was initially the province of the elite, but in the aftermath of Marabout War the ruling class increasingly rejected it while it become more and more widespread among the ruled. The Brak himself converted only in the 19th century.[26]

Economy

[edit]Waalo played an integral role in the slave trade in the Senegal river valley, with most captives coming from regions upriver, often captured in war or slaving raids. Other trade goods included gum arabic, leather, and ivory, as well as the foodstuffs, primarily millet upon which Saint-Louis depended.[27]

Waalo was paid fees for every boatload of gum arabic or slaves that was shipped on the river, in return for its "protection" of the trade.[28]

Kings of Waalo

[edit]In all, Waalo had 52 kings since its founding. Names and dates taken from John Stewart's African States and Rulers (1989).[29]

| # | Name | Reign Start | Reign End |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | N'Dya-N'Dya | 1186 | 1202 |

| 2 | Mbang Waad | 1202 | 1211 |

| 3 | Barka Mbody | 1211 | 1225 |

| 4 | Tyaaka Mbar | 1225 | 1242 |

| 5 | unknown | 1242 | 1251 |

| 6 | Amadu Faaduma | 1251 | 1271 |

| 7 | Yerim Mbanyik | 1271 | 1278 |

| 8 | Tyukuli | 1278 | 1287 |

| 9 | Naatago Tany | 1287 | 1304 |

| 10 | Fara Yerim | 1304 | 1316 |

| 11 | Mbay Yerim | 1316 | 1331 |

| 12 | Dembaane Yerim | 1331 | 1336 |

| 13 | N'dyak Kumba Sam Dyakekh | 1336 | 1343 |

| 14 | Fara Khet | 1343 | 1348 |

| 15 | N'dyak Kumba-gi tyi Ngelogan | 1348 | 1355 |

| 16 | N'dyak Kumba-Nan Sango | 1355 | 1367 |

| 17 | N'dyak Ko N'Dyay Mbanyik | 1367 | 1380 |

| 18 | Mbany Naatago | 1380 | 1381 |

| 19 | Meumbody N'dyak | 1381 | 1398 |

| 20 | Yerim Mbanyik Konegil | 1398 | 1415 |

| 21 | Yerim Kode | 1415 | 1485 |

| 22 | Fara Toko | 1485 | 1488 |

| 23 | Fara Penda Teg Rel | 1488 | 1496 |

| 24 | Tykaaka Daro Khot | 1496 | 1503 |

| 25 | Naatago Fara N'dyak | 1503 | 1508 |

| 26 | Naatago Yerim | 1508 | 1519 |

| 27 | Fara Penda Dyeng | 1519 | 1531 |

| 28 | Tani Fara N'dyak | 1531 | 1542 |

| 29 | Fara Koy Dyon | 1542 | 1549 |

| 30 | Fara Koy Dyop | 1549 | 1552 |

| 31 | Fara Penda Langan Dyam | 1552 | 1556 |

| 32 | Fara Ko Ndaama | 1556 | 1563 |

| 33 | Fara Aysa Naalem | 1563 | 1565 |

| 34 | Naatago Kbaari Daaro | 1565 | 1576 |

| 35 | Beur Tyaaka Loggar | 1576 | 1640 |

| 36 | Yerim Mbanyik Aram Bakar | 1640 | 1674 |

| 37 | Naatago Aram Bakar | 1674 | 1708 |

| 38 | N'dyak Aram Bakar Teedyek | 1708 | 1733 |

| 39 | Yerim N'date Bubu | 1733 | 1734 |

| 40 | Meu Mbody Kumba Khedy | 1734 | 1735 |

| 41 | Yerim Mbanyik Anta Dyop | 1735 | |

| 42 | Yerim Khode Fara Mbuno | 1735 | 1736 |

| 43 | N'dyak Khuri Dyop | 1736 | 1780 |

| 44 | Fara Penda Teg Rel | 1780 | 1792 |

| 45 | N'dyak Kumba Khuri Yay | 1792 | 1801 |

| 46 | Saayodo Yaasin Mbody | 1801 | 1806 |

| 47 | Kruli Mbaaba | 1806 | 1812 |

| 48 | Amar Faatim Borso | 1812 | 1821 |

| 49 | Yerim Mbanyik Teg | 1821 | 1823 |

| 50 | Fara Penda Adam Sal | 1823 | 1837 |

| 51 | Kherfi Khari Daano | 1837 | 1840 |

| 52 | Mbeu Mbody Maalik | 1840 | 1855 |

References

[edit]- ^ a b Dieng, Bassirou; Kesteloot, Lilyan (2009). Les épopées d'Afrique noire: Le myth de Ndiadiane Ndiaye. Paris: Karthala. p. 255. ISBN 978-2811102104.

- ^ a b Boulegue 2013, p. 39.

- ^ Seck, Ibrahima, '‘The French Discovery of Senegal: Premises for a Policy of Selective Assimilation', in Toby Green (ed.), Brokers of Change: Atlantic Commerce and Cultures in Pre-Colonial Western Africa, Proceedings of the British Academy (London, 2012; online edn, British Academy Scholarship Online, 31 Jan. 2013), https://doi.org/10.5871/bacad/9780197265208.003.0016, accessed 29 Sept. 2024.

- ^ Boulegue 2013, p. 20.

- ^ Sarr, Alioune, "Histoire du Sine-Saloum (Sénégal)", in Bulletin de l'IFAN, tome 46, série B, nos 3-4, 1986–1987. p. 19

- ^ Ndiaye, Bara (2021). "Le Jolof: Naissance et Evolution d'un Empire jusqu'a la fin du XVIIe siecle". In Fall, Mamadou; Fall, Rokhaya; Mane, Mamadou (eds.). Bipolarisation du Senegal du XVIe - XVIIe siecle (in French). Dakar: HGS Editions. p. 187.

- ^ Boulegue 2013, p. 57.

- ^ Boulegue 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Boulègue, Jean (1987). Le Grand Jolof, (XVIIIe - XVIe Siècle). Paris: Karthala Editions. p. 63.

- ^ Davis, p. 198.

- ^ Boulegue 2013, p. 150.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 134.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 116.

- ^ Davis, p. 169.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 148–50.

- ^ Webb 1995, p. 40.

- ^ Barry 1992, p. 280.

- ^ a b Barry 1992, p. 281.

- ^ a b Webb 1995, p. 42.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 195–99.

- ^ Colvin, Lucie Gallistel (1974). "ISLAM AND THE STATE OF KAJOOR: A CASE OF SUCCESSFUL RESISTANCE TO JIHAD" (PDF). Journal of African History. xv (4): 604. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ Sheldon, Kathleen (2016). Historical Dictionary of Women in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 179.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 284–9.

- ^ Weikert, Imche (2013). "Les souveraines dans les systèmes politiques duaux en Afrique: L'exemple de la lingeer au Sénégal". In Fauvelle-Aymar, François-Xavier; Hirsch, Bertrand (eds.). Les ruses de l'historien. Essais d'Afrique et d'ailleurs en hommage à Jean Boulègue. Hommes et sociétés (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions. pp. 15–29. doi:10.3917/kart.fauve.2013.01.0015. ISBN 978-2-8111-0939-4. S2CID 246907590.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 189.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 157.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 120–5.

- ^ Barry 1972, p. 127.

- ^ Stewart, John (1989). African States and Rulers. London: McFarland. p. 288. ISBN 0-89950-390-X.

Bibliography

[edit]- Barry, Boubacar (1972). Le royaume du Waalo: le Senegal avant la conquete. Paris: Francois Maspero.

- Barry, Boubacar (1992). "Senegambia from the sixteenth to the eighteenth century: evolution of the Wolof, Sereer and 'Tukuloor'". In Ogot, B. A. (ed.). General History of Africa vol. V: Africa from the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century. UNESCO. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- Barry, Boubacar. 'The Subordination of Power and Mercantile Economy: The Kingdom of Waalo 1600-1831 "in The Political Economy of Under-Development, Dependence in Senegal by Rita Cruise O'Brien (Ed.) Sage Series on African Mod. and Dev., Vol. 3. California. pp. 39–63.

- Boulegue, Jean (2013). Les royaumes wolof dans l'espace sénégambien (XIIIe-XVIIIe siècle) (in French). Paris: Karthala Editions.

- Davis, R. Hunt (ed.). Encyclopedia Of African History And Culture, Vol. 2 (E-book ed.). The Learning Source. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- Webb, James (1995). Desert frontier : ecological and economic change along the Western Sahel, 1600-1850. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0299143309. Retrieved 25 December 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- WORLD STATESMEN.org Senegal Traditional States

- Présentation du pays at the website of the national office of statistics, La République Islamique de Mauritanie : www.ons.mr.

- Ndete Yalla, dernière reine du Walo (Sénégal). Extrait du portrait de cette reine sénégalaise du 19e siècle que nous dresse Sylvia Serbin dans son ouvrage « Reines d’Afrique et héroïnes de la diaspora noire » (Editions Sépia) Par Sylvia Serbin.

- NDIOURBEL: Première capital du Waalo[permanent dead link] in Sites et Monuments historiques du Senegal, Center of Resources for the Emergence of Social Participation, Senegal.